Market Correction: What Does It Mean?

A volatile mix of concerns over tariffs, inflation, and economic growth, as well as uncertainty about the future direction of government policy, pushed several major U.S. stock indexes into correction territory in mid-March—meaning they had fallen more than 10% from a recent high.

"Correction" is fairly neutral term for what can be an unpleasant experience. But what does it mean? And, more importantly, what might happen afterward and how can you help your portfolio weather the downturn? Here are answers to some commonly asked questions:

What is a correction?

There's no universally accepted definition of a correction, but most people consider a correction to have occurred when a major stock index, such as the S&P 500® Index or Dow Jones Industrial Average, declines by more than 10% (but less than 20%—that would be a bear market, but more on that below) from its most recent peak. It's called a correction because historically the drop often "corrects" and returns prices to their longer-term trend.

Do corrections mark the start of a bear market?

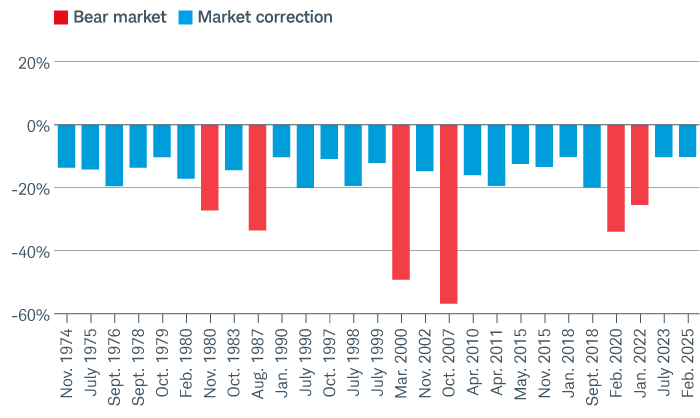

Nobody can predict with any degree of certainty whether a correction will reverse or turn into a bear market (that is, periods when the market is down by 20% or more). If it's any consolation, historically most corrections haven't become bear markets. There have been 27 market corrections since November 1974—including the current one—and only six of them became bear markets (which began in 1980, 1987, 2000, 2007, and 2020).

Since 1974, only six market corrections have become bear markets

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research with data provided by Morningstar, Inc.

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research with data provided by Morningstar, Inc. Each period listed represents the beginning month/year of either a market correction or a bear market. The general definition of a market correction is a market decline that is more than 10%, but less than 20%. A bear market is usually defined as a decline of 20% or greater. The market is represented by the S&P 500 index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly.

But what if it really is the start of a bear market?

Bear markets are unpleasant, but the fact is that they occur periodically throughout virtually every investor's lifetime.

It's also helpful to keep them in perspective. Since 1966, the average bear market has lasted roughly 14 months, far shorter than the average bull market. And they often end as abruptly as they began, with a quick rebound that is very difficult to predict—a case in point is the S&P 500's pandemic-fueled bear market in early 2020, which lasted a mere 33 days from the previous high on February 19 to the trough on March 23. That's why long-term investors are usually better off staying the course and not pulling money out of the market, as long as their situation hasn't changed.

Past bear markets have tended to be shorter than bull markets

![[Alt text: Bar chart displays S&P 500 peak-to-trough or trough-to-peak price returns from 1961 through 2024.]](https://international.schwab.com/sites/g/files/eyrktu651/files/bear%20markets%20have%20tended%20to%20be%20shorter%20than%20bull%20markets.png)

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research with data provided by Bloomberg. Data as of 12/31/2024.

Chart displays S&P 500 peak-to-trough or trough-to-peak price returns from 12/12/1961 to 12/31/2024. The market is represented by daily price returns of the S&P 500 index. Price return does not include the effects of reinvested cash. Bear markets are defined as periods with cumulative declines of at least 20% from the previous peak close. Its duration is measured as the number of days from the previous peak close to the lowest close reached after it has fallen at least 20%, and includes weekends and holidays. Periods between bear markets are designated as bull markets. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs, and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. For more information on indexes, please see schwab.com/indexdefinitions. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Investing involves risk, including loss of principal.

What should I do now?

Worrying excessively about a bear market can be counterproductive, but being prepared for one is always a good idea. Consider investing strategies that potentially could help your portfolio—and your emotional wellbeing—in case of a significant downturn. Here are some additional steps all investors should consider:

- If you don't have a financial plan, consider making one. A written financial plan can help you craft an appropriately balanced portfolio. It can also calm your nerves and make it easier to stay the course when markets get bumpy. The idea here is that knowing you're financially prepared for a downturn can help you stomach them when they arrive.

- Review your risk tolerance. It's relatively easy to take risks when the market is rising, but market downturns sometimes can be a wake-up call to consider adjusting your target asset allocation. Consider how much loss you have the emotional and financial capacity to handle.

- Rebalance regularly. Market changes can skew your allocation from its original target. Over time, assets that have gained in value will account for more of your portfolio, while those that have declined will account for less. Rebalancing means selling positions that have become overweight in relation to the rest of your portfolio, and moving the proceeds to positions that have become underweight. It's a good idea to rebalance at regular intervals.

- Take your age into consideration. If you're a younger investor saving for a goal that is 15 or more years away, you have time to potentially recover from a market drop. However, the picture may change for investors nearing or in retirement. Regular rebalancing and appropriate diversification are important for you at this stage, and your risk profile typically will become more conservative as retirement approaches. If you've recently retired and begun to withdraw from your portfolio, you also should be aware that poor returns in the early years of retirement can have a very negative effect on a portfolio; consider taking steps to avoid selling assets in a down market, such as reducing your planned withdrawals or postponing large expenses.