Party in the USA: Election Facts

We make it a habit not to wade into partisan politics, so consider this election-related report more of a "fact sheet." As an addendum for readers who like to go deeper into the weeds of election-related policy proposals (including on taxes), we would point readers to the excellent work of our colleague Mike Townsend, Managing Director of Legislative and Regulatory Affairs (2024 Election: A Look at Candidates' Tax Proposals and 2024 Election: What Investors Should Know).

It is what it is

Below, we cover historical economic performance over the post-WWII period (since 1948), as well as stock market performance over the full span of the S&P 500 (since 1928). Let's start with the economy, via a look at average gross domestic product (GDP) and personal consumption expenditures (PCE). The U.S. economy is a massive and complex system and we certainly don't credit—or blame—presidents for everything that occurs in the economy. That said, both measures of growth have fared better when Democrats were in the White House.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 6/30/2024. PCE represents personal consumption expenditures.

For what it's worth, of the 14 recessions experienced by the U.S. economy in the post-WWII period, 12 started with Republicans in the White House and two started with Democrats in the White House. On the other side of that coin, recessions obviously end, and of those 14 recessions, 10 ended under Republican presidents and four ended under Democratic presidents.

Next, we can look at the unemployment rate, which on average started lower under Republican presidents than under Democrats. However, on average, the unemployment rate rose under Republicans and fell under Democrats. More specifically, the unemployment rate did not rise under any Democratic president during the post-WWII period, while it rose under all but one Republican president.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 8/31/2024. Data for Truman begins in 1948.

Let's move on to the stock market. The table below shows every presidential administration over the full history of the S&P 500, broken out by each of the four years of election cycles. Important caveat: Even more so when analyzing stock market behavior, it's foolish to put outsized weight on political party and its influence on a market that has primary drivers well outside the bounds of politics.

That said, here's the data. As shown via the summary rows at the bottom, stocks have performed better in all four cycle years under Democratic presidents. Regardless of the party in the White House, the pre-election year has historically been most rewarding for investors, with the strongest average returns and the highest percentage of positive outcomes. So far in this cycle, the market has been somewhat on point with a week 2022 (the mid-term year), a strong 2023 (the pre-election year), but somewhat out of character this year given the market's strong performance so far.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 12/31/2023.

Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Our friends at Ned Davis Research created the handy table below—using the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which goes all the way back to 1900. Because the party controlling the White House is not the only story, NDR broke it down into all six possible outcomes, showing real (inflation-adjusted) returns for the Dow. As shown, the best performance historically was when a Democrat was in the White House, but Congress was split (also the best outcome in the post-WWII era). An important caveat is that that breakdown historically occurred less than 5% of the time. The next-best performance—with a much higher percentage of time—was when a Republican was in the White House and Republicans also controlled Congress. On the other side of the coin, the worst performance historically was when a Republican was in the White House alongside a split Congress (the second-worst outcome in the post-WWII era).

Source: Charles Schwab, ©Copyright 2024 Ned Davis Research, Inc.

Further distribution prohibited without prior permission. All Rights Reserved. See NDR Disclaimer at www.ndr.com/copyright.html. For data vendor disclaimers refer to www.ndr.com/vendorinfo/. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Sectors say: "It's the economy"

Keeping on the theme of not tying broad market performance in with who takes control of the White House, we think the same rings true when it comes to sectors. While it's tempting to forecast leadership shifts based on potential policies of an administration, it often ends up being a fool's errand. History shows macroeconomic forces are often much more important in determining sector behavior, evidenced by this next visual.

The quilt chart below shows sector performance in every election year going back to 1992 (GICS sector data does not go back further). There are a handful of takeaways from this. Primarily, there is no consistency when it comes to leadership. Yes, Tech holds the status of being the best performer for three election years (2024 is not complete yet, of course), but it also experienced dramatic declines in 2000 and 2008–bringing its average performance to 3.6% across all election years, putting it in seventh place.

Perhaps equally as fascinating is the fact that traditional defensive sectors have experienced better performance (on average) relative to the dominant growth trio (Tech, Communication Services, and Consumer Discretionary), which has been a major force in the post-pandemic era. That doesn't necessarily mean election years are de facto risk-off. Consider the fact that the best years for Consumer Staples and Utilities were 2008 and 2000, respectively; the former was marked by the bursting of the housing bubble while the latter the bursting of the tech and telecom bubble.

No rhyme for sectors and elections

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, *as of 9/27/2024.

**Averages shown are simple averages for election years only and do not include 2024 due to the year not being over. Sector performance is represented by price returns of the following 11 GICS sector indices: Consumer Discretionary Sector, Consumer Staples Sector, Energy Sector, Financials Sector, Health Care Sector, Industrials Sector, Information Technology Sector, Materials Sector, Real Estate Sector, Communication Services Sector, and Utilities Sector. Returns of the broad market are represented by the S&P 500. As of 9/28/2018, GICS broadened the Telecommunications sector and renamed it Communications Services. This reclassified some companies from the Consumer Discretionary sector to the new Communications Services sector. Past data has been updated to reflect the changes. Although the Real Estate Sector was launched in September 2016, Standard & Poor's and Bloomberg provide historical data starting from October 2001. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The average column also emphasizes the reality that there is, on average, no consistency in leadership when it comes to election years. The Financials sector (which is in the cyclical camp) has had the best average performance, but right behind it are two defensive sectors (Staples and Utilities) and then another cyclical (Industrials). Yet, there are also deeper cyclicals (Materials and Energy) holding up the rear. The fact that one has to work hard to identify a performance pattern in the above quilt is proof that diversification—across and within sectors— can be an effective strategy and, while there are no guarantees of future performance, one we believe investors should consider, especially in an election year.

A "political" vs. "partisan" Fed

One of the more frustrating aspects of the current election cycle is the notion that the Federal Reserve is letting politics come into play when making policy decisions, with some arguing that the Fed was being political by starting its easing campaign in order to influence election results. We put no credence into that thinking.

Yes, from a structural standpoint, the Fed is technically a political body. It is the U.S. Congress that establishes the Fed's mandates; the president of the United States nominates the Board of Governors, including the chair and the vice chair. Given the president and members of Congress are elected by U.S. citizens, there is an inherent political aspect to the Fed's structure.

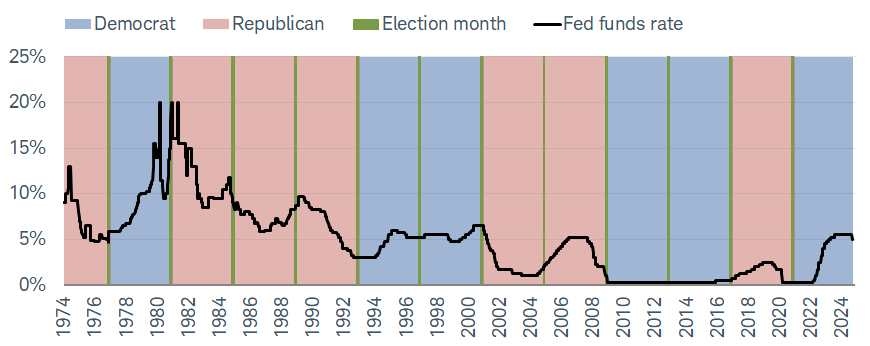

That does not mean the Fed is partisan, though, especially when it comes to setting monetary policy. Presidential elections don't play a role in monetary policy decisions; in fact, it was often the case throughout history that the Fed adjusted policy in presidential election years. Shown in the chart below—created by our colleague Cooper Howard—is the fact that since 1976, there has been only one election year in which the Fed did not adjust policy at all: 2012. Both were consistent with the low-inflation, post-Global Financial Crisis era in which the Fed was trying to keep rates lower for longer in hopes of getting inflation back up. How times have changed.

Elections don't influence Fed moves

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of 9/27/2024.

Blue shaded areas represent Democratic president. Red shaded areas represent Republican president.

Here is the real point, though. It is not out of bounds for the Fed to adjust policy close to—or in—the month of the election. The Fed cut rates in the month of the election in 1976 and 1984; it hiked rates in the month of the election in 1980 and 2004. Even looking at past Septembers, there were cuts in 1992 and 2024, and there were hikes in 1980 and 2004.

That should put to bed the notion that the Fed's most recent rate cut, as well as the prospect that more cuts are coming this year, was partisan in nature. For all the criticism Fed members have received over the past couple years, it's difficult to say they have been lacking in telegraphing their moves well in advance. In our view, thinking that monetary policy is driven by elections and partisanship won't serve investors well, not least because it is empirically false.

The ultimate exclamation point

As we're equity market strategists, let's bring this report home with another broad take on historic market performance. Again, using the post-WWII period, an investor who put $10,000 into the S&P 500 at the beginning of 1948 would have seen that grow to about $312,000 by the end of 2023 if the money was only in the market under Republican presidents. Conversely, $10,000 grew to more than $1.2 million by the end of last year when only invested under Democratic presidents.

Time IN the market

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research with data provided by Morningstar, Inc.

The above chart shows what a hypothetical portfolio value would be if an investor invested $10,000 in a portfolio that tracks the Ibbotson U.S. Large Stock Index on 1/1/1948 under three different scenarios. The first two scenarios are what would occur if an investor only invested when one particular party was president. The third scenario is what would occur if an investor had stayed invested throughout the entire period. Returns include reinvestment of dividends and interest. The example is hypothetical and provided for illustrative purposes only. It is not intended to represent a specific investment product. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur management fees, costs and expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Shame on anyone stopping the analysis there by exclaiming that investors would have been much better off only investing when Democrats were in the White House. An investor who did not care whether the Oval Office was painted blue or red, and kept their money in the market, saw that initial investment grow to nearly $38 million. I don't know about any of you, but I'll take the $38 million and let the $1.2 million and $300,000 folks duke it out.